If you are a vocalist, live sound technician, studio engineer or just looking to do a bit of home recording, knowing what to look for in a new microphone is an important task.

There is a huge variety of brands available, and each with their own subtle differences that can be used to create different sounds (without even touching on the world of older, vintage microphones).

However, all of these tend to fall into one of a few categories of microphone type.

Learning the basics of how these work, and what makes them best suited for the task will be of benefit to most musicians.

We teamed up with producer/sound engineer, Sonix endorsee and session percussionist/ drummer extraordinaire Daniel J Logan of Orchard Studios to bring you some information on a few of the common types.

Microphone Basics

What a microphone does, in essence, is convert physical pressure waves to electronic signal.

This analogue signal will then travel, via cable, to it’s destination. Be that an outboard pre-amp that will amplify the signal (essentially turning up the volume) for recording or off to a mixing desk for live sound.

Polar patterns

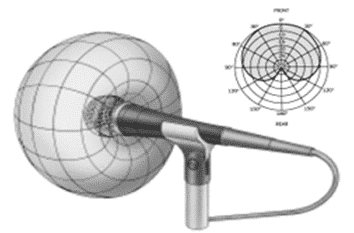

One of ways of possibly categorizing microphones is by their polar pattern. Put simply, the polar pattern of a microphone is the area or direction of sound it will capture. Some will be designed to pick up very specific areas; others will capture more of the general ambience.

Omnidirectional: These microphones pick up sound from all around them. In practice, this means whether you sing or speak at it from the left, right (or any other direction) the microphone should hear you evenly.

Bidirectional: Also known as figure of eight microphones, bidirectional pick up sensitive sound from the front and back, but poorly from the sides.

Unidirectional: Generally picking up sound from one direction, unidirectional microphones (such as the ever popular Shure SM58) are the workhorse’s of the music industry. The microphone will pick up sound that is ‘on axis’ to it, i.e. where it is pointed, providing quality results in a variety of different scenarios.Vocals

The Bandeoke Band always use dynamic mics like the Shure SM58 for vocals… and they are a band that need a lot of microphones!

When choosing a vocal microphone, there are several very important factors to consider, but first a musician should decide whether it is destined for use in the studio or live.

As a general rule for any live situation, it’s always recommended that singers own their own vocal microphone. This is not only to maintain hygiene but also to ensure that a quality sound is achieved at every gig – you will know how to get the best out of your microphone.

Dynamic microphones are the most common type of microphone chosen by singers for live performance, as they are both durable and more affordable.

Industry standard microphones from companies such as Shure and Sennheiser are popular choices for both professionals and amateurs.

Dan says:

In recent years there have been more examples of live condenser microphones coming to the market, such as the Neumann KMS 105, but due to the problem of feedback with the more sensitive condenser circuitry, the majority of stage vocal mics are dynamic.

If you are recording at home, a condenser microphone such as Aston Origin or Audio Technica T2020 should produce a good sound, due to their sensitivity and extremely high sound quality.

Dan says:

There is always a balance to strike when recording at home. As condenser microphones are far more sensitive to sound (and are generally more delicate) than dynamic microphones, people often have problems when using them in untreated or badly soundproofed rooms. Common problems include the sound of the central heating or the next door neighbours having a row getting onto the recording! I usually suggest that a decent dynamic (such as the Shure SM57 or Beyerdynamic TG150d) often provide more useable results when recording at home.

When choosing a studio condenser microphone, it is important to notice that they require phantom power, provided by a mixer or a preamp (usually marked +48v or Phantom).

Some condensers, such as the AKG C1000 use an internal battery to supply their power.

Dan says:

Whether live or in the studio, the choice of vocal microphone has a great impact on the final sound. At the studios, we have a variety of high quality microphones, both dynamic and condenser, as different voices will suit different models. When choosing a vocal mic for stage use it’s always best to ask your local music shop to let you try out some different ones. Although by far the most common microphone is the Shure SM58, there are singers I know who much prefer models from EV, Neumann or Sennehiser for their voice. This is not to knock the SM58, and it may well be the one that’s perfect for your voice, but it’s always best to try out a few before you buy.

Drums

Drums are one of the more complicated instruments to mic up, due to their size and range of volumes.

For a basic live set up, a pair of well-placed condenser microphones over the top of the kit, a dynamic microphone for the snare and a kick/bass drum mic is a pretty common set up.

This allows you (or the engineer) to have control over all the main aspects of the kit and create an effective front of house mix. More advanced set ups may also add microphones to the toms and high hat for added control.

When recording in the studio, it is more common to use a wider selection of drum microphones for toms and even under and above the snare.

For specific drums, these will tend to be unidirectional, with a tight polar pattern therefore minimising the “bleed” (the amount of unwanted sound from other parts of the kit).

However, it is also common to use a condenser as a “Room Mic” to capture the overall sound of the kit from several paces away.

For a bass drum, a low frequency microphone such as a D112 is suitable, whilst condenser microphones are still best for cymbals.

Dan says:

There are so many different ways (and so many differing views) as to how to mic up a drum kit it would be impossible to mention them all here. However, the first thing to think about is that a good drummer will ‘balance’ the kit themselves, meaning they will keep the relative volumes of each drum equal, expect when they choose to go softer or stronger for effect. With this in mind, sometimes overheads are all you need to capture a good sound.

It is also genre-specific to some extent. I’d use a mic on each drum for a pop or rock record but I sometimes use the minimalist approach when I’m recording jazz albums (though I usually use a kick and snare mic too, just in case!) As a drummer and percussion player, when I play live I always try to provide the engineer with a tech sheet; detailing what instruments I’ll be playing, in advance (particularly if it’s a big venue or festival where more control may be needed by the engineer for their FOH mix). I also usually bring along a couple of my own microphones for some of the more unusual parts of my kit, in case it’s helpful.

Guitars

When mic’ing up electric guitar amplifiers, the first step is to locate the speaker. This may not be immediately obvious if your speaker cover is opaque, but if your amp (or cabinet) is open backed, you should be able to see inside. Failing that, a quick google search will do the job.

For recording or live, the simplest way to get a good sound from your electric guitar is to use a dynamic microphone (like an SM57).

There are several different theories for mic placement (so make sure you play around to achieve the best sound) but slightly offset from the speaker cone is a good place to start.

Recording acoustic guitars is slightly more complicated, and many engineers will prefer a combination of condenser and dynamic microphones, with one angled at the sound hole and another towards the start of the neck.

What brands of microphones do you recommend and for what? Let us know in the comments below…

Share this: